WW II and Beyond - The War Effort and Post-War Boom

1940 - 1952

By the end of 1939 prosperity in America had begun to improve as the country steadily emerged from the depression. Employment was up and optimism was returning to daily life. At Studebaker, the resounding success of the Champion had given the company new life. Throughout the rest of the world though, the situation was grave. Hitler's armies were rolling over Europe while the Japanese consumed Asia and the Pacific.

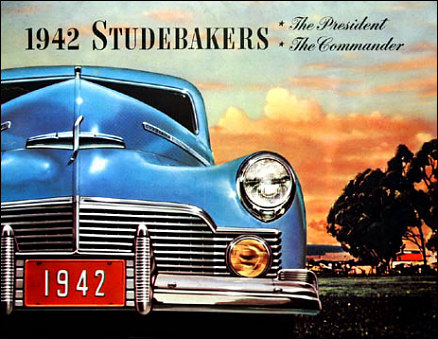

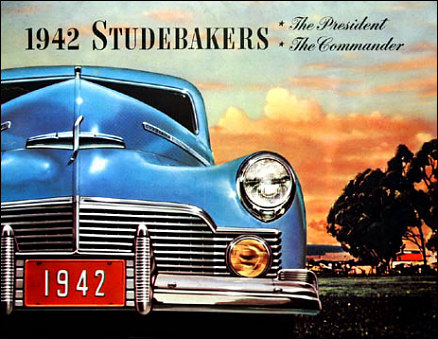

1942 was the last year for passenger vehicles before Studebaker turned to war production.

Foreign orders for war supplies were again coming into South Bend. In 1939 Studebaker sold large numbers of K30 three ton trucks to France, Belgium and Holland who adapted them to military use until the fall of the continent in 1940. A large number of these Studebaker trucks were captured by German forces at the Battle of Dunkirk and many of them were later converted to run on synthetic fuel. China too needed trucks but purchased chassis and fitted their own cabs and bodies and used them on the Burma Road. Even with tensions mounting as they were, most Americans opposed the idea of becoming involved in a foreign war. Congress too, resisted any suggestion of involvement but prudently increased defense funding. With production costs rising and certain that civilian car production would be reduced, Vance actively sought military contracts. When the U. S. Government approached several auto makers seeking proposals for military trucks, Studebaker created a truck based on their M series and early in 1941 was given a contract to begin production. In December 1941, as the next years models were just coming off assembly lines, peace for America finally ran out.

When America entered the conflict, the nations industrial base quickly shifted to making the implements of war. Studebaker's contribution to the war effort would be in the production of three principle items, trucks, aircraft engines and a little tracked vehicle called the Weasel. Shortly before the war, Studebaker had already started limited production of its US6 truck for the Army. When passenger car production was halted on January 31, 1942, truck assembly was stepped up reaching 4,000 per month by March. Powered by a six cylinder Hercules engine, the US6 trucks were produced in four and six wheel drive versions. 200,000 of these rugged vehicles were built between 1941 and 1945 for the US and Soviet Armies and approximately half of Studebakers trucks went to the Soviet Union under Lend Lease. They were so abundant there that ‘Studebaker’ became Russian slang for truck.

The US6 factored heavily in Studebaker's war production.

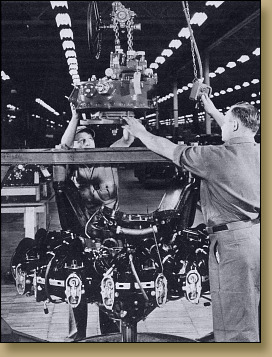

Prior to Americas entry into the war, Studebaker had contracted with the government to manufacture large numbers of the Wright Cyclone R-1820 radial engine. Due to the perceived urgency in the last months before the war, the government financed construction of three new factories to be located in South Bend, Fort Wayne and Chicago. By June 1942, the South Bend plant was completed and fully operational. Built under license, the 1,200 horse power engines were used in the famed Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress

Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress . Studebakers output of these critical engines would top 63,000 by wars end.

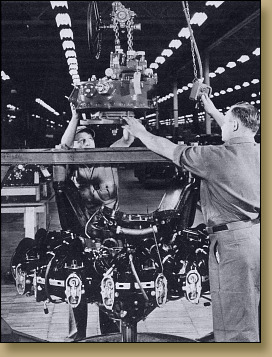

Workers assemble a radial engine for the B-17 Flying Fortress.

The Weasel was originally conceived as a snow vehicle. The concept for the Weasel received resistance in the beginning, but was eventually approved with the assistance of Dwight Eisenhower, then in the War Plans Division. When Studebaker received the contract in May of 1942 they immediately went to work. Utilizing a Champion 6 cylinder engine and other automotive components, the first version carried the Army designation M28. The initial reactions to the Weasel were lukewarm as it had questionable handling characteristics in snow and frequently threw it’s tracks. When it was discovered however, the little vehicle could go almost anywhere, Army officials were encouraged. Studebaker set about redesigning it, moving the engine from back to front and improving other design flaws. The new version, designated the M29 worked beautifully on all terrains. Used in Europe and the Pacific, the military relied heavily on the Weasel and continued their use after the war. The last version, the M29C, was amphibious and found extensive use in the Pacific. By VJ day, over 15,000 Weasels had been built.

A Studebaker built M-29 Weasel.

As the war neared an end, industry began to prepare for peace. Studebakers postwar transition however, began long before hostilities ended. Realizing the first auto maker to offer a completely new model would reap substantial benefits, Studebaker set a goal to be first and the wisdom of this strategy has long been debated. Those against the decision argue that Studebaker should have maximized profits with the warmed over 1942 models for at least another year or two.

As early as 1943 a few individuals in the company were assigned to design and planning for the 're-conversion' to passenger cars. Tooling for the new model, it was realized, would take time and could not be accomplished while the war was still going on. It was decided therefore, to initially produce the 1942 models with superficial changes until preparations for a completely new model could begin. As the war neared an end it became clear that 1947 would be the target year for a new model.

In December of 1945 production of civilian vehicles resumed with the '46 Skyway Champion, in reality the reworked '42. Studebaker produced a little over 10,000 '46s before shutting the lines down three months later to begin preparations for the '47 production run. By April of 1946 the all new '47s were announced with the slogan “First by far with a postwar car”. Studebaker took body styling into a new domain with the ‘47s and Raymond Loewy is credited with the overall design of the pace setting '47s. However, some of the detail design of the new Studebakers was actually accomplished by Virgil Exner. Exner had worked for Loewy but was fired when their egos clashed. Chief Engineer Roy E. Cole, who disliked Loewy, hired Exner on the sly having him work from his home. To ensure Exner's success, Cole then fed bogus specifications to Loewy. When it was discovered that much of Loewy’s design had incorrect measurements it was too late to do anything but use Exner's covert design. To appease Loewy, Studebaker gave him full credit. Some sources suggest that from the cowl forward is Exner's design.

A 1947 Studebaker Starlight Champion Coupe. Was it coming or going?

With the '47s, previously pronounced fenders were replaced by a streamlined body and the passenger compartment of some models featured wrap around rear windows. The new shape inspired the famous comment that one couldn’t tell if it was coming or going. As expected, they were a hit with the public and demand was phenomenal. Total sales for 1947 neared $268,000,000 for a profit of $9,100,000. Studebaker had come a long way since receivership, fourteen years earlier.

The immediate postwar years for Studebaker would be unrivalled in the companies history. With profits rising and demand at an all time high, production capacity needed to be increased. In the postwar years raw materials, especially steel, were still hard to obtain and as a consequence, Studebaker purchased the Empire Steel Corporation of Mansfield, Ohio in 1947. That same year a new factory was acquired in Hamilton, Ontario and in 1948 one of the aviation plants used to make bomber engines during the war was converted to vehicle manufacture. 1948 would also bring a major management change when Paul Hoffman departed the company on a five year leave of absence to head the Economic Cooperation Administration, part of the Marshall Plan When Truman first asked Hoffman to join the ECA, Hoffman was undecided and told the President he needed time to disciss it with family and associates. Later that day, before Hoffman could make any calls, Truman announced that the new ECA head would be Paul Hoffman thus drafting him.. In Hoffman's absence, Vance assumed the duties of both President and Chairman of the Board. By 1950 America was at war in Korea and so was Studebaker. The Korean War would not be the all effort of the decade before and for most Americans, life went on as usual. Studebaker's part in that conflict would consist of building military trucks and J-47 turbojet aircraft engines.

When Truman first asked Hoffman to join the ECA, Hoffman was undecided and told the President he needed time to disciss it with family and associates. Later that day, before Hoffman could make any calls, Truman announced that the new ECA head would be Paul Hoffman thus drafting him.. In Hoffman's absence, Vance assumed the duties of both President and Chairman of the Board. By 1950 America was at war in Korea and so was Studebaker. The Korean War would not be the all effort of the decade before and for most Americans, life went on as usual. Studebaker's part in that conflict would consist of building military trucks and J-47 turbojet aircraft engines.

The 1950 models featured the famous bullet nose.

1950 was also the year of the bullet-nose design, arguably the most recognizable Studebaker ever made. The bullet-nose created quite a stir when it was introduced, prompting both praise and humor. Bullet noses were featured on the '48 Tucker and '49 Ford suggesting Studebaker copied the theme. In reality, Loewy's designers had prepared concept drawings as early as '41 and a mockup was constructed during the war in '43. The Ford bullet nose, in fact, traces its origins to Loewy's South Bend studio where Robert Bourke and Holden Koto, working on the side, designed the Ford bullet nose for 1949. In the end, the public seemed to love it because Studebaker production reached a peak that year with 268,229 cars, the most the company would ever build in a single year.

1951 was charged with anticipation. The next year would be Studebakers centennial and preparations were well underway but the big news for now was a new engine. In its 99th year Studebaker introduced their first overhead valve V-8. Initially offered in the ‘51 Commander, the new engine displaced 232 cubic inches and developed 120 horse power. The public loved the high performance engine and Commander sales were understandably brisk. Total production that year however, tapered. In fact sales figures for 1951, presented a paradox. For the first time its history Studebaker grossed over $500,000,000 but profits were down to $12,500,000, half of the previous years net. This was due in part to wartime price controls but more importantly a substantial amount of the years sales revenue was derived from government contracts. Only in hind sight can we see the beginning of a trend that would lead to eventual downfall. For now though, everything seemed fine and the coming year would bring a milestone and celebration.

Studebaker introduced a sleek, new body style in it's centennial year. Shown is the 52 V8 Commander Starliner.

With the arrival of 1952 Studebaker celebrated its first 100 years of business. Raymond Loewy and Robert Bourke planned to introduce an all new design for the centennial year but delays necessitated going with a more conventional design. Nonetheless the celebration went on and the successors to the Studebaker brothers and the citizens of South Bend celebrated the milestone with enthusiasm. Parades were given, books were written and memorabilia of all descriptions was handed out. Studebaker even provided the pace car for the Indianapolis 500. At the University of Notre Dame a celebration featured a multitude of speakers and a choir sang Rolling Along for a Hundred Years, written for the occasion. The people who then made up Studebaker were justly proud to have arrived at that point. Of the 5000 wagon makers that comprised Studebakers competition, only Studebaker survived. And, in the course of its first century, Studebaker had sold $6 billion worth of vehicles for a profit of $300 million. The people of Studebaker proudly stood ready to embark on another 100 years.

The Studebaker Centennial logo.

The ominous trend of the year before would continue in 1952. On the surface everything appeared fine. Total sales for the company reached a record $586,000,000 that year. But beneath the apparent prosperity automobile sales continued to slump and profits amounted to a mere $14,300,000. Government contracts still accounted for high sales figures. Over the last century government contracts had always allowed the company to grow and indeed, many of these contracts came at crucial times for Studebaker. In the past though, Studebaker had always terminated government dealings and returned exclusively to vehicle production as soon as they could.

The Decline and Fall of Studebaker

1953 - 1966

Studebaker had a long tradition of survival and had weathered many calamities over the years. Yet, as the euphoria of the centennial faded, the company was facing a situation more dangerous than it had ever encountered. The record sales of 1950 had dropped sharply by 1953-54. Studebaker's share of the market was down and meager profits had now turned to loss. Since 1950 the board at Studebaker had repeatedly turned down Vance's requests to modernize factory facilities and instead payed out gracious dividends. Ford and GM, on the other hand, were spending vast sums on modernization. Adding fuel to the fire were Studebaker's labor costs. Their employees were the best paid in the industry and though the company had always enjoyed good relations with labor, Studebaker's more than fair treatment of it's work force was now crippling the company.

Studebaker was not the only car maker whose profits had dwindled; all of the independent manufacturers found themselves in similar circumstances. Where they had benefited in the post war years, they now faced a crisis. The only solution was merger. In 1953 Kaiser and Willys-Overland joined forces and concentrated on producing the Jeep. Then Hudson and Nash merged to form American Motors. Studebaker too was looking at a merger.

The '53 models were some of Studebaker's most stylish ever.

On the positive side, the '53 Commander was a sensation when it was revealed. The timeless lines of this beautiful vehicle were the creation of Robert Bourke, Loewy's chief South Bend designer and the new car was low, sleek and aerodynamic. Industry periodicals praised the forward thinking "European" design and eyes were more than raised at GM.

In 1954 Studebaker and Packard began talks on the possibility of merging but it quickly became clear that while Packard was in favor of a merger, they would not move forward until Studebaker brought it's labor costs down. The problem at hand was two fold. Studebakers were more expensive than their Ford / GM counterparts and Studebaker employees on average received 20% higher wages than the rest of the industry. Additionally, reports were now filtering in that suggested that the quality of the much vaunted '53 models was lacking. The labor situation needed a major overhaul.

In 1954 the longest and bitterest labor negotiations at Studebaker Corporation began. Management believed that the very survival of Studebaker was in the balance but they needed to convince labor. During the talks management took the unprecedented step of opening company books to labor. It was clear that costs had to be reduced. After three months of negotiations an agreement was reached that reduced wages by 18%. Labor had insisted on concessions to offset the cuts but when the workers were briefed on the contract, all hell broke loose and the contract was voted down. Management retaliated by stating it's intention to terminate the contract and then published ads in South Bend news papers explaining the company's position. Once the rank and file understood how critical labor costs were to the survival of Studebaker, they voted to accept.

Negotiating the new labor agreement paved the way to merge with Packard. The newly organized Studebaker-Packard Corporation was to be headed by James J. Nance, head of Packard, who assumed the roles of President and CEO. Hoffman, who had now returned from government duties, became Chairman of the Board and Vance took on Chairman of the Executive Committee.

Prior to Packard, Nance had headed GE Hotpoint where he had built up Hotpoint from an obscure appliance maker to the number three appliance company in the market. Investors and observers alike felt his no non-sense leadership would turn Studebaker around. What he encountered at South Bend was a company steeped in tradition. A tradition going back to the Studebaker brothers themselves who had always saw to it that their employees were well cared for. As Nance implemented what he felt were necessary changes, he encountered resistance from Studebaker personnel including Vance and Hoffman. As long as Nance's changes involved the executive staff he seemed to be on solid ground but attempts to "improve" work rules and standards among rank and file met with resistance and ultimately fueled slowdowns, work stoppages and a general strike lasting 36 days in early 1955.

Even though the strike was settled, Studebaker workers were still enraged about the changes Nance continued to seek and numerous wild cat strikes ensued. Studebaker workers had become so unruly that when it came time to negotiate a contract, the International AUW leadership itself sat at the bargaining table. In the end Nance got his way, with some concessions, and personal time was reduced and the practice of bumping eliminated In a union, bumping is the practice of filling a vacant job with the most senior person next in line. This in turn creates a vacancy as that person moves up, etc, etc..

In a union, bumping is the practice of filling a vacant job with the most senior person next in line. This in turn creates a vacancy as that person moves up, etc, etc..

The 1956 Golden Hawk.

Nance now had the labor situation more or less to his liking but the company continued on a downward spiral losing $29,000,000 in 1955. Studebakers were still more expensive than their Ford / GM counterparts but lacked any features to account for that. As a cost saving measure, the '56 models featured a superficial face lift over '55s and introduced one completely new model, the Loewy designed Hawk. This was to no avail. As first quarter 1956 sales figures became available it was apparent the crisis had worsened. To add to the dilemma, the lucrative jet engine contract with the Defense Department was canceled. Matters had become so dismal that the possibility of liquidation and bankruptcy became all too real. The Eisenhower administration even expressed concern over the situation. Eisenhower was not willing to reverse the cancellation of the jet engine contract but did see to it that Studebaker received an order for 5,000 trucks.

In April of 1956 a panel of consultants advised Nance to liquidate. This precipitated high level meetings in Detroit and Washington that included, among others, the Secretary of Defense, the Secretary of the Treasury, Curtis-Wright and several investment firms. Weeks of discussion finally produced a solution. In addition to new financing from several banks and insurance company's, Curtis-Wright agreed to oversee management of Studebaker-Packard and received the option of purchasing 5 million shares of unissued S-P stock; a new subsidiary corporation to handle defense contracts, Utica-Bend, was formed; and finally, Studebaker-Packard was given distribution rights for Daimler-Benz. All of this was done without approval of share holders, a patently illegal move motivated by urgency. When the dust settled, James Nance, Harold Vance and Paul Hoffman, along with others, resigned from Studebaker-Packard. Nance had been at Studebaker a mere sixteen months and his brief tenure is still debated. Some point to his accomplishments, breaking labor, reducing wages and trimming executive staff as positive moves. Others insist he raped the company by destroying a proud tradition and left the company in much worse shape than he found it.

Harold Churchill, a thirty year Studebaker engineer, took the reigns from Nance. His approach would be much different than his predecessor. He steered the company away from "head on competition with the big three." In 1957 he introduced the Scotsman, a stripped down Champion sans accessories, and priced it below anything comparable on the market. It quickly became Studebaker's best seller. Encouraged by this approach, Churchill decided on the same gamble that had saved Studebaker in the depression. A low priced car. In 1939 the Champion had brought Studebaker back to being the number one independent. Interestingly, Churchill had worked on the Champion project.

It was hoped that the low priced Lark would save Studebaker. Shown here, a 1960 Lark.

At the end of 1958 the new 'economy car' was introduced to the public. The Lark, was affordably priced and attractive and sales were brisk. The rising popularity of the Hawk combined with the new Lark increased Studebaker's share and put the company in the black once again. South Bend was jubilant as their company had once again returned from the brink and 3,000 jobs had opened up at the factory. The board realized this was a temporary victory and expected sales to drop once the Big Three introduced low priced cars.

In view of this upturn, the corporation quickly refinanced it's debt and set in motion a new strategy for survival. Not necessarily the survival of Studebaker cars but the corporation itself. It was apparent that Studebaker could no longer compete in the automobile business as it once had. The key to the survival of the corporation lay in diversification.

Management was sharply divided on key issues of diversification and as a result, the process did not proceed smoothly. Some felt Studebaker should continue to make cars while diversifying. Others felt Studebaker was doomed as an auto maker and should pump everything into acquiring other companies. The differences led to bickering then open hostility. One can only imagine what a more unified vision might have led to into terms of number and quality of companies acquired.

After four years of diversification Studebaker's holdings included, among others -

In late 1960, with profits just teetering in the black, the board elected Sherwood Egbert as CEO, a former Marine officer who had distinguished himself at McCulloch Corporation. Throughout his tenure at Studebaker, he was hampered by an ongoing battle with cancer .

Egbert was young and cocky and attempted to present himself as concerned with the rank and file. They weren't impressed. Egbert seemed to be singing the same mantra as those who came before him - labor must make concessions in the interest of survival. Understandably, they felt they had heard this before. On January 1, 1962 Studebaker workers embarked on the longest strike in the company's history. Egbert and the board held their ground. After 38 days the union caved in and had little show for their effort.

Egbert, who had no prior experience in the automotive industry, did keep the assembly lines rolling when many in management wanted to stop production. He was determined to keep Studebaker's automobile line alive and conceived a bold plan that represented Studebaker's last hope. A plan that seemed incredulous. In addition to occupying the low end of the price market, he felt Studebaker should make a bid for the performance market as well. To this end, he enlisted designer Raymond Loewy and developed the Avanti. It was introduced in the spring of '62 and once again Studebaker was at the forefront of automobile design. The excitement generated by the Avanti in trade publications and car shows was offset when Studebaker encountered production problems and deliveries ran behind. The Avanti was mechanically sound and in fact, Andy Granatelli established 29 new world land speed records for stock, off-the-showroom cars in the Avanti. The problem was encountered when workers attempted to fit the fiberglass body parts together; something that Studebaker had no experience with. The earliest production Avantis were so poorly fitted that the rear window popped out at high speed.

Struggling with cancer throughout his tenure at Studebaker, Egbert valiantly tried to keep Studebaker's car line alive. By late '63 however, Egbert was on permanent medical leave and it was apparent from recent sales figures that automobiles were no longer viable for the corporation. The board had planned to announce the closure of the South Bend plant in late December however, they were upstaged on December 9 by the South Bend Tribune who had got wind of the plan. A press conference was called where it was confirmed that the plant would close but, executives added, the Hamilton, Ontario plant would continue to make Larks. On December 20, 1963, the last Studebaker produced at South Bend, a red Lark Daytona, rolled off the line. A little over two years later, the Hamilton plant also ceased production of Studebaker vehicles bringing a long tradition to an end. The continued manufacturing of cars in Canada had been a ploy by the Studebaker board to sidestep their obligation to dealers.

Epilogue

Though the assembly lines had become quiet, Studebaker continued on in the form of a closed investment group. Like the fish who is swallowed by a larger fish, who in turn is swallowed by a larger fish, what remained of Studebaker passed from buyer to buyer until it vanished. It has now returned in the form of Studebaker-Worthington Leasing. However, the blood line from Studebaker Corporation to Studebaker-Worthington is so tenuous it can hardly be considered a descendant.

The end of Studebaker was not a heroic fight to the death but a scene of ignominious retreat wherein the General and his staff are saved and the army is lost. The stewards of Studebaker, in my opinion, were more concerned with getting while the getting's good than preserving the auto manfacturer they worked for. One is left to wonder what might have happened had they focused their energy on selling cars and keeping the assembly lines open. The 'all or nothing' spirit demonstrated by Harold Vance and Paul Hoffman during the depression may well have saved the company again in the '60s.

1940 - 1952

By the end of 1939 prosperity in America had begun to improve as the country steadily emerged from the depression. Employment was up and optimism was returning to daily life. At Studebaker, the resounding success of the Champion had given the company new life. Throughout the rest of the world though, the situation was grave. Hitler's armies were rolling over Europe while the Japanese consumed Asia and the Pacific.

1942 was the last year for passenger vehicles before Studebaker turned to war production.

Foreign orders for war supplies were again coming into South Bend. In 1939 Studebaker sold large numbers of K30 three ton trucks to France, Belgium and Holland who adapted them to military use until the fall of the continent in 1940. A large number of these Studebaker trucks were captured by German forces at the Battle of Dunkirk and many of them were later converted to run on synthetic fuel. China too needed trucks but purchased chassis and fitted their own cabs and bodies and used them on the Burma Road. Even with tensions mounting as they were, most Americans opposed the idea of becoming involved in a foreign war. Congress too, resisted any suggestion of involvement but prudently increased defense funding. With production costs rising and certain that civilian car production would be reduced, Vance actively sought military contracts. When the U. S. Government approached several auto makers seeking proposals for military trucks, Studebaker created a truck based on their M series and early in 1941 was given a contract to begin production. In December 1941, as the next years models were just coming off assembly lines, peace for America finally ran out.

When America entered the conflict, the nations industrial base quickly shifted to making the implements of war. Studebaker's contribution to the war effort would be in the production of three principle items, trucks, aircraft engines and a little tracked vehicle called the Weasel. Shortly before the war, Studebaker had already started limited production of its US6 truck for the Army. When passenger car production was halted on January 31, 1942, truck assembly was stepped up reaching 4,000 per month by March. Powered by a six cylinder Hercules engine, the US6 trucks were produced in four and six wheel drive versions. 200,000 of these rugged vehicles were built between 1941 and 1945 for the US and Soviet Armies and approximately half of Studebakers trucks went to the Soviet Union under Lend Lease. They were so abundant there that ‘Studebaker’ became Russian slang for truck.

The US6 factored heavily in Studebaker's war production.

Prior to Americas entry into the war, Studebaker had contracted with the government to manufacture large numbers of the Wright Cyclone R-1820 radial engine. Due to the perceived urgency in the last months before the war, the government financed construction of three new factories to be located in South Bend, Fort Wayne and Chicago. By June 1942, the South Bend plant was completed and fully operational. Built under license, the 1,200 horse power engines were used in the famed Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress

Workers assemble a radial engine for the B-17 Flying Fortress.

The Weasel was originally conceived as a snow vehicle. The concept for the Weasel received resistance in the beginning, but was eventually approved with the assistance of Dwight Eisenhower, then in the War Plans Division. When Studebaker received the contract in May of 1942 they immediately went to work. Utilizing a Champion 6 cylinder engine and other automotive components, the first version carried the Army designation M28. The initial reactions to the Weasel were lukewarm as it had questionable handling characteristics in snow and frequently threw it’s tracks. When it was discovered however, the little vehicle could go almost anywhere, Army officials were encouraged. Studebaker set about redesigning it, moving the engine from back to front and improving other design flaws. The new version, designated the M29 worked beautifully on all terrains. Used in Europe and the Pacific, the military relied heavily on the Weasel and continued their use after the war. The last version, the M29C, was amphibious and found extensive use in the Pacific. By VJ day, over 15,000 Weasels had been built.

A Studebaker built M-29 Weasel.

As the war neared an end, industry began to prepare for peace. Studebakers postwar transition however, began long before hostilities ended. Realizing the first auto maker to offer a completely new model would reap substantial benefits, Studebaker set a goal to be first and the wisdom of this strategy has long been debated. Those against the decision argue that Studebaker should have maximized profits with the warmed over 1942 models for at least another year or two.

As early as 1943 a few individuals in the company were assigned to design and planning for the 're-conversion' to passenger cars. Tooling for the new model, it was realized, would take time and could not be accomplished while the war was still going on. It was decided therefore, to initially produce the 1942 models with superficial changes until preparations for a completely new model could begin. As the war neared an end it became clear that 1947 would be the target year for a new model.

In December of 1945 production of civilian vehicles resumed with the '46 Skyway Champion, in reality the reworked '42. Studebaker produced a little over 10,000 '46s before shutting the lines down three months later to begin preparations for the '47 production run. By April of 1946 the all new '47s were announced with the slogan “First by far with a postwar car”. Studebaker took body styling into a new domain with the ‘47s and Raymond Loewy is credited with the overall design of the pace setting '47s. However, some of the detail design of the new Studebakers was actually accomplished by Virgil Exner. Exner had worked for Loewy but was fired when their egos clashed. Chief Engineer Roy E. Cole, who disliked Loewy, hired Exner on the sly having him work from his home. To ensure Exner's success, Cole then fed bogus specifications to Loewy. When it was discovered that much of Loewy’s design had incorrect measurements it was too late to do anything but use Exner's covert design. To appease Loewy, Studebaker gave him full credit. Some sources suggest that from the cowl forward is Exner's design.

A 1947 Studebaker Starlight Champion Coupe. Was it coming or going?

With the '47s, previously pronounced fenders were replaced by a streamlined body and the passenger compartment of some models featured wrap around rear windows. The new shape inspired the famous comment that one couldn’t tell if it was coming or going. As expected, they were a hit with the public and demand was phenomenal. Total sales for 1947 neared $268,000,000 for a profit of $9,100,000. Studebaker had come a long way since receivership, fourteen years earlier.

The immediate postwar years for Studebaker would be unrivalled in the companies history. With profits rising and demand at an all time high, production capacity needed to be increased. In the postwar years raw materials, especially steel, were still hard to obtain and as a consequence, Studebaker purchased the Empire Steel Corporation of Mansfield, Ohio in 1947. That same year a new factory was acquired in Hamilton, Ontario and in 1948 one of the aviation plants used to make bomber engines during the war was converted to vehicle manufacture. 1948 would also bring a major management change when Paul Hoffman departed the company on a five year leave of absence to head the Economic Cooperation Administration, part of the Marshall Plan

The 1950 models featured the famous bullet nose.

1950 was also the year of the bullet-nose design, arguably the most recognizable Studebaker ever made. The bullet-nose created quite a stir when it was introduced, prompting both praise and humor. Bullet noses were featured on the '48 Tucker and '49 Ford suggesting Studebaker copied the theme. In reality, Loewy's designers had prepared concept drawings as early as '41 and a mockup was constructed during the war in '43. The Ford bullet nose, in fact, traces its origins to Loewy's South Bend studio where Robert Bourke and Holden Koto, working on the side, designed the Ford bullet nose for 1949. In the end, the public seemed to love it because Studebaker production reached a peak that year with 268,229 cars, the most the company would ever build in a single year.

1951 was charged with anticipation. The next year would be Studebakers centennial and preparations were well underway but the big news for now was a new engine. In its 99th year Studebaker introduced their first overhead valve V-8. Initially offered in the ‘51 Commander, the new engine displaced 232 cubic inches and developed 120 horse power. The public loved the high performance engine and Commander sales were understandably brisk. Total production that year however, tapered. In fact sales figures for 1951, presented a paradox. For the first time its history Studebaker grossed over $500,000,000 but profits were down to $12,500,000, half of the previous years net. This was due in part to wartime price controls but more importantly a substantial amount of the years sales revenue was derived from government contracts. Only in hind sight can we see the beginning of a trend that would lead to eventual downfall. For now though, everything seemed fine and the coming year would bring a milestone and celebration.

Studebaker introduced a sleek, new body style in it's centennial year. Shown is the 52 V8 Commander Starliner.

With the arrival of 1952 Studebaker celebrated its first 100 years of business. Raymond Loewy and Robert Bourke planned to introduce an all new design for the centennial year but delays necessitated going with a more conventional design. Nonetheless the celebration went on and the successors to the Studebaker brothers and the citizens of South Bend celebrated the milestone with enthusiasm. Parades were given, books were written and memorabilia of all descriptions was handed out. Studebaker even provided the pace car for the Indianapolis 500. At the University of Notre Dame a celebration featured a multitude of speakers and a choir sang Rolling Along for a Hundred Years, written for the occasion. The people who then made up Studebaker were justly proud to have arrived at that point. Of the 5000 wagon makers that comprised Studebakers competition, only Studebaker survived. And, in the course of its first century, Studebaker had sold $6 billion worth of vehicles for a profit of $300 million. The people of Studebaker proudly stood ready to embark on another 100 years.

The Studebaker Centennial logo.

The ominous trend of the year before would continue in 1952. On the surface everything appeared fine. Total sales for the company reached a record $586,000,000 that year. But beneath the apparent prosperity automobile sales continued to slump and profits amounted to a mere $14,300,000. Government contracts still accounted for high sales figures. Over the last century government contracts had always allowed the company to grow and indeed, many of these contracts came at crucial times for Studebaker. In the past though, Studebaker had always terminated government dealings and returned exclusively to vehicle production as soon as they could.

The Decline and Fall of Studebaker

1953 - 1966

Studebaker had a long tradition of survival and had weathered many calamities over the years. Yet, as the euphoria of the centennial faded, the company was facing a situation more dangerous than it had ever encountered. The record sales of 1950 had dropped sharply by 1953-54. Studebaker's share of the market was down and meager profits had now turned to loss. Since 1950 the board at Studebaker had repeatedly turned down Vance's requests to modernize factory facilities and instead payed out gracious dividends. Ford and GM, on the other hand, were spending vast sums on modernization. Adding fuel to the fire were Studebaker's labor costs. Their employees were the best paid in the industry and though the company had always enjoyed good relations with labor, Studebaker's more than fair treatment of it's work force was now crippling the company.

Studebaker was not the only car maker whose profits had dwindled; all of the independent manufacturers found themselves in similar circumstances. Where they had benefited in the post war years, they now faced a crisis. The only solution was merger. In 1953 Kaiser and Willys-Overland joined forces and concentrated on producing the Jeep. Then Hudson and Nash merged to form American Motors. Studebaker too was looking at a merger.

The '53 models were some of Studebaker's most stylish ever.

On the positive side, the '53 Commander was a sensation when it was revealed. The timeless lines of this beautiful vehicle were the creation of Robert Bourke, Loewy's chief South Bend designer and the new car was low, sleek and aerodynamic. Industry periodicals praised the forward thinking "European" design and eyes were more than raised at GM.

In 1954 Studebaker and Packard began talks on the possibility of merging but it quickly became clear that while Packard was in favor of a merger, they would not move forward until Studebaker brought it's labor costs down. The problem at hand was two fold. Studebakers were more expensive than their Ford / GM counterparts and Studebaker employees on average received 20% higher wages than the rest of the industry. Additionally, reports were now filtering in that suggested that the quality of the much vaunted '53 models was lacking. The labor situation needed a major overhaul.

In 1954 the longest and bitterest labor negotiations at Studebaker Corporation began. Management believed that the very survival of Studebaker was in the balance but they needed to convince labor. During the talks management took the unprecedented step of opening company books to labor. It was clear that costs had to be reduced. After three months of negotiations an agreement was reached that reduced wages by 18%. Labor had insisted on concessions to offset the cuts but when the workers were briefed on the contract, all hell broke loose and the contract was voted down. Management retaliated by stating it's intention to terminate the contract and then published ads in South Bend news papers explaining the company's position. Once the rank and file understood how critical labor costs were to the survival of Studebaker, they voted to accept.

Negotiating the new labor agreement paved the way to merge with Packard. The newly organized Studebaker-Packard Corporation was to be headed by James J. Nance, head of Packard, who assumed the roles of President and CEO. Hoffman, who had now returned from government duties, became Chairman of the Board and Vance took on Chairman of the Executive Committee.

Prior to Packard, Nance had headed GE Hotpoint where he had built up Hotpoint from an obscure appliance maker to the number three appliance company in the market. Investors and observers alike felt his no non-sense leadership would turn Studebaker around. What he encountered at South Bend was a company steeped in tradition. A tradition going back to the Studebaker brothers themselves who had always saw to it that their employees were well cared for. As Nance implemented what he felt were necessary changes, he encountered resistance from Studebaker personnel including Vance and Hoffman. As long as Nance's changes involved the executive staff he seemed to be on solid ground but attempts to "improve" work rules and standards among rank and file met with resistance and ultimately fueled slowdowns, work stoppages and a general strike lasting 36 days in early 1955.

Even though the strike was settled, Studebaker workers were still enraged about the changes Nance continued to seek and numerous wild cat strikes ensued. Studebaker workers had become so unruly that when it came time to negotiate a contract, the International AUW leadership itself sat at the bargaining table. In the end Nance got his way, with some concessions, and personal time was reduced and the practice of bumping eliminated

The 1956 Golden Hawk.

Nance now had the labor situation more or less to his liking but the company continued on a downward spiral losing $29,000,000 in 1955. Studebakers were still more expensive than their Ford / GM counterparts but lacked any features to account for that. As a cost saving measure, the '56 models featured a superficial face lift over '55s and introduced one completely new model, the Loewy designed Hawk. This was to no avail. As first quarter 1956 sales figures became available it was apparent the crisis had worsened. To add to the dilemma, the lucrative jet engine contract with the Defense Department was canceled. Matters had become so dismal that the possibility of liquidation and bankruptcy became all too real. The Eisenhower administration even expressed concern over the situation. Eisenhower was not willing to reverse the cancellation of the jet engine contract but did see to it that Studebaker received an order for 5,000 trucks.

In April of 1956 a panel of consultants advised Nance to liquidate. This precipitated high level meetings in Detroit and Washington that included, among others, the Secretary of Defense, the Secretary of the Treasury, Curtis-Wright and several investment firms. Weeks of discussion finally produced a solution. In addition to new financing from several banks and insurance company's, Curtis-Wright agreed to oversee management of Studebaker-Packard and received the option of purchasing 5 million shares of unissued S-P stock; a new subsidiary corporation to handle defense contracts, Utica-Bend, was formed; and finally, Studebaker-Packard was given distribution rights for Daimler-Benz. All of this was done without approval of share holders, a patently illegal move motivated by urgency. When the dust settled, James Nance, Harold Vance and Paul Hoffman, along with others, resigned from Studebaker-Packard. Nance had been at Studebaker a mere sixteen months and his brief tenure is still debated. Some point to his accomplishments, breaking labor, reducing wages and trimming executive staff as positive moves. Others insist he raped the company by destroying a proud tradition and left the company in much worse shape than he found it.

Harold Churchill, a thirty year Studebaker engineer, took the reigns from Nance. His approach would be much different than his predecessor. He steered the company away from "head on competition with the big three." In 1957 he introduced the Scotsman, a stripped down Champion sans accessories, and priced it below anything comparable on the market. It quickly became Studebaker's best seller. Encouraged by this approach, Churchill decided on the same gamble that had saved Studebaker in the depression. A low priced car. In 1939 the Champion had brought Studebaker back to being the number one independent. Interestingly, Churchill had worked on the Champion project.

It was hoped that the low priced Lark would save Studebaker. Shown here, a 1960 Lark.

At the end of 1958 the new 'economy car' was introduced to the public. The Lark, was affordably priced and attractive and sales were brisk. The rising popularity of the Hawk combined with the new Lark increased Studebaker's share and put the company in the black once again. South Bend was jubilant as their company had once again returned from the brink and 3,000 jobs had opened up at the factory. The board realized this was a temporary victory and expected sales to drop once the Big Three introduced low priced cars.

In view of this upturn, the corporation quickly refinanced it's debt and set in motion a new strategy for survival. Not necessarily the survival of Studebaker cars but the corporation itself. It was apparent that Studebaker could no longer compete in the automobile business as it once had. The key to the survival of the corporation lay in diversification.

Management was sharply divided on key issues of diversification and as a result, the process did not proceed smoothly. Some felt Studebaker should continue to make cars while diversifying. Others felt Studebaker was doomed as an auto maker and should pump everything into acquiring other companies. The differences led to bickering then open hostility. One can only imagine what a more unified vision might have led to into terms of number and quality of companies acquired.

After four years of diversification Studebaker's holdings included, among others -

|

STP, Engine oil additives Clarke Floor Machines Gravely Tractors Onan, Engines and Generators Schaefer, Commercial Refrigeration Studebaker of Canada, Automobile Manufacturing Studegrip, Tire Studs Franklin, Appliances |

In late 1960, with profits just teetering in the black, the board elected Sherwood Egbert as CEO, a former Marine officer who had distinguished himself at McCulloch Corporation. Throughout his tenure at Studebaker, he was hampered by an ongoing battle with cancer .

Egbert was young and cocky and attempted to present himself as concerned with the rank and file. They weren't impressed. Egbert seemed to be singing the same mantra as those who came before him - labor must make concessions in the interest of survival. Understandably, they felt they had heard this before. On January 1, 1962 Studebaker workers embarked on the longest strike in the company's history. Egbert and the board held their ground. After 38 days the union caved in and had little show for their effort.

Egbert, who had no prior experience in the automotive industry, did keep the assembly lines rolling when many in management wanted to stop production. He was determined to keep Studebaker's automobile line alive and conceived a bold plan that represented Studebaker's last hope. A plan that seemed incredulous. In addition to occupying the low end of the price market, he felt Studebaker should make a bid for the performance market as well. To this end, he enlisted designer Raymond Loewy and developed the Avanti. It was introduced in the spring of '62 and once again Studebaker was at the forefront of automobile design. The excitement generated by the Avanti in trade publications and car shows was offset when Studebaker encountered production problems and deliveries ran behind. The Avanti was mechanically sound and in fact, Andy Granatelli established 29 new world land speed records for stock, off-the-showroom cars in the Avanti. The problem was encountered when workers attempted to fit the fiberglass body parts together; something that Studebaker had no experience with. The earliest production Avantis were so poorly fitted that the rear window popped out at high speed.

Struggling with cancer throughout his tenure at Studebaker, Egbert valiantly tried to keep Studebaker's car line alive. By late '63 however, Egbert was on permanent medical leave and it was apparent from recent sales figures that automobiles were no longer viable for the corporation. The board had planned to announce the closure of the South Bend plant in late December however, they were upstaged on December 9 by the South Bend Tribune who had got wind of the plan. A press conference was called where it was confirmed that the plant would close but, executives added, the Hamilton, Ontario plant would continue to make Larks. On December 20, 1963, the last Studebaker produced at South Bend, a red Lark Daytona, rolled off the line. A little over two years later, the Hamilton plant also ceased production of Studebaker vehicles bringing a long tradition to an end. The continued manufacturing of cars in Canada had been a ploy by the Studebaker board to sidestep their obligation to dealers.

Epilogue

Though the assembly lines had become quiet, Studebaker continued on in the form of a closed investment group. Like the fish who is swallowed by a larger fish, who in turn is swallowed by a larger fish, what remained of Studebaker passed from buyer to buyer until it vanished. It has now returned in the form of Studebaker-Worthington Leasing. However, the blood line from Studebaker Corporation to Studebaker-Worthington is so tenuous it can hardly be considered a descendant.

The end of Studebaker was not a heroic fight to the death but a scene of ignominious retreat wherein the General and his staff are saved and the army is lost. The stewards of Studebaker, in my opinion, were more concerned with getting while the getting's good than preserving the auto manfacturer they worked for. One is left to wonder what might have happened had they focused their energy on selling cars and keeping the assembly lines open. The 'all or nothing' spirit demonstrated by Harold Vance and Paul Hoffman during the depression may well have saved the company again in the '60s.

| More Illustrations |