The Golden Age - Exceptional Growth and Weathering the Depression

1919 - 1939

The United States came through ‘The Great War’ with a sense of accomplishment. Now it was time to resume the ‘pursuit of happiness’. By 1919, horse drawn vehicle production was curtailed except for farm wagons and in 1920 Studebaker sold the wagon works to The Kentucky Wagon Mfg Co of Louisville. Everything pertaining to wagon and carriage manufacture was turned over including existing inventories of wagons. The remaining equipment, facilities and personnel were shifted to automobile production. In so doing, Studebaker became the only wagon maker to successfully transition to automobiles.

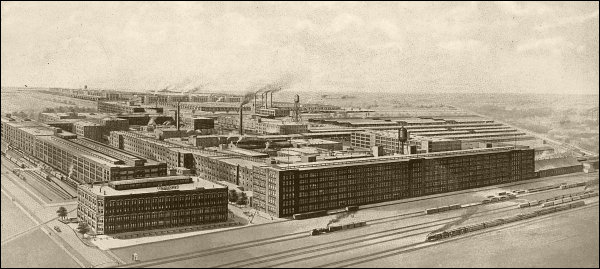

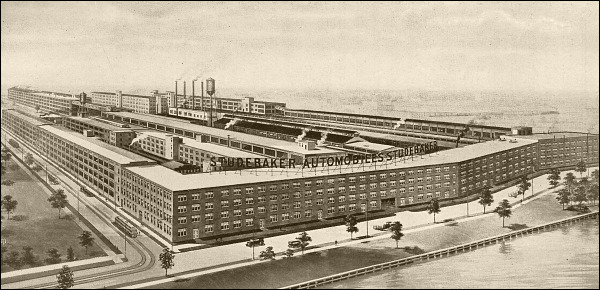

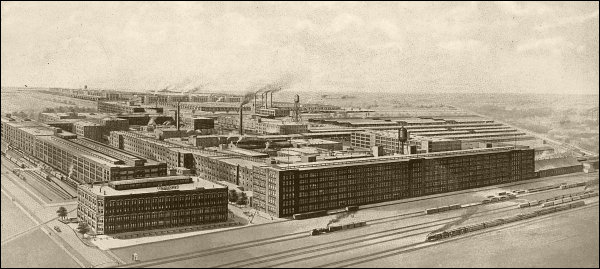

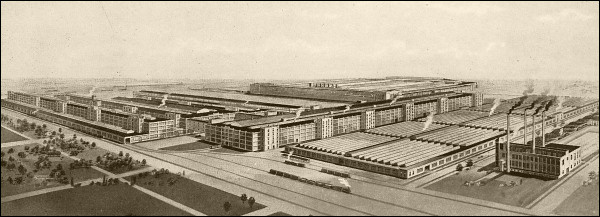

South Bend Plant 1 in the early 1920s. ( enlarge )

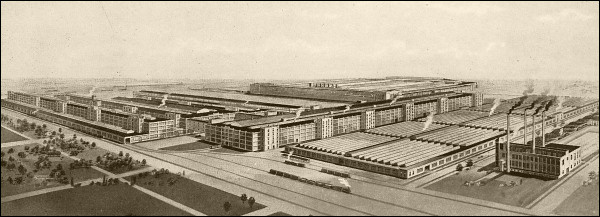

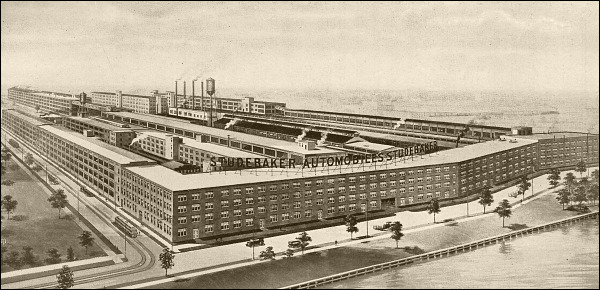

South Bend Plant 2 in the early 1920s. ( enlarge )

Up until 1920, all of Studebaker’s automobiles were being built at the former EMF factories in Detroit. Erskine’s pre-war plan to expand the South Bend factory had to be put on hold til war’s end with facilities only partiality complete. In march of 1919, construction resumed and by April of 1920 Plant 2 began the production of automobiles in South Bend. Plant 2 was an industrial show piece where most everything required to assemble cars was fabricated on site. The Detroit plant continued to produce the majority of Studebakers cars but, plans were made to eventually move a larger share of automobile assembly to South Bend.

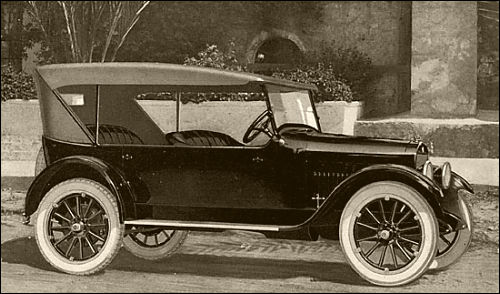

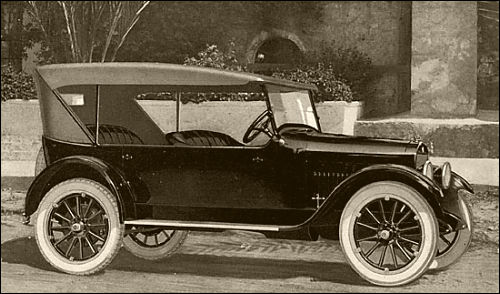

The Light Six helped establish Studebaker's reputation.

Beginning in 1918 and continuing into the next decade, Studebaker built it's reputation around a line of six cylinder vehicles that vitalized it's growth. The `Big Six' was the deluxe series. It had a 60 hp engine and was offered as a tourer, sedan or coupe. The `Special Six' series was similar but was priced lower with a 50 hp engine. The `Light Sixes' were slightly smaller and economically priced with a 40 hp engine. Growth with Erskine at the helm was exceptional and the popularity of the sixes was evident as 51,000 automobiles were sold in 1920, 65,000 in 1921 and 150,000 in 1923. Commenting on the Sixes, Erskine said "these are the cars that made Studebaker famous".

Atalanta adorned the radiators of Studebaker's luxury line.

Detroit Plant 3 was eventually moved to South Bend. ( enlarge )

In 1926 the Detroit plant was finally relocated to South Bend. The man in charge was Harold Vance, who had been General Sales Manager since '23. With the move, he was promoted to Vice President for Production and Engineering and elected to the Board. That year another important addition was made to the executive staff. Out in Los Angles, a gentleman named Paul Hoffman

Paul G. Hoffman

1891 - 1974 had built the largest and most successful dealership in the country and was invited to South Bend to become Vice President in Charge of Sales. Several years before Hoffman assumed the Vice President position he had gone to South Bend having won a sales essay contest. During his visit he was introduced to J. M. who asked him if he would like to know why Studebaker had become so successful. When Hoffman replied to the affirmative, J. M. told him it was because they "always gave more than they promised". After a brief pause J. M. added "but don't give them too much or you'll go broke".

The 1927 Studebaker Erskine

With ample profits coming in, Studebaker sought to expand it's established line of models. Seeing the success of Ford’s Model-T and responding to consumer research and requests from dealers (even in Europe), Erskine felt Studebaker should enter the low price market and accordingly had engineers develop the ‘Erskine’. This handsome, little car, introduced in 1927, had a 40 horse power engine delivering 60 m.p.h. and 30 miles to the gallon but it was never the success it was hoped to be. A short engine life and a significantly higher price tag than it’s competitors added up to poor sales and the Erskine was discontinued within three years. Albert Erskine's venture in the opposite direction would prove to be more fruitful.

1931 President Eight State Brougham

1928 was a banner year for Studebaker. The poor showing in the small car market the previous year, would be offset by a development just coming to fruition. Concurrent with the little ‘Erskine’, Studebaker had been working on it’s first entry into the 8 cylinder market. Chief Engineer Delmar 'Barney' Roos, who had joined the company in 1926, was given the task of building a big 8 cylinder car and he gave Studebaker a genuine classic, the President 8 Barney Roos would later design the engine for the Jeep.. These large, well appointed cars utilized Studebakers first high compression engines and they were noted for their roominess, style and speed. As the model continued into the early 30s, it’s lines and amenities became even more refined. Whats more, with a price tag around $2000, they were within reach of those looking at mid-priced cars. Noted for performance as well as style, Presidents established over 100 records for speed and endurance, some of which stood more than three decades later. That same year, another companies misfortune turned to Studebakers advantage. The prestigious luxury car maker, Pierce Arrow was desperately short of capital and approached Erskine with a proposal to merge. Realizing the prominence this would bring, he readily agreed and the deal was closed. Within a year of merging, Pierce Arrow sales increased 78% largely due to Studebaker's expansive sales and distribution network. Studebaker and the rest of the country approached 1929 stable and prosperous.

Barney Roos would later design the engine for the Jeep.. These large, well appointed cars utilized Studebakers first high compression engines and they were noted for their roominess, style and speed. As the model continued into the early 30s, it’s lines and amenities became even more refined. Whats more, with a price tag around $2000, they were within reach of those looking at mid-priced cars. Noted for performance as well as style, Presidents established over 100 records for speed and endurance, some of which stood more than three decades later. That same year, another companies misfortune turned to Studebakers advantage. The prestigious luxury car maker, Pierce Arrow was desperately short of capital and approached Erskine with a proposal to merge. Realizing the prominence this would bring, he readily agreed and the deal was closed. Within a year of merging, Pierce Arrow sales increased 78% largely due to Studebaker's expansive sales and distribution network. Studebaker and the rest of the country approached 1929 stable and prosperous.

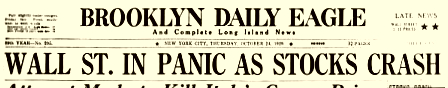

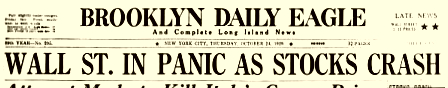

As the 20’s drew to an end America enjoyed unparalleled affluence. 1929 began on a financial upswing reaching a peak in late summer when the stock market topped out at an all time high. Then, early in October, stock prices began to drop. By October 22, banks and corporations nervously called in outstanding loans. Stockholders reacted in panic and frantically sold their holdings. Within two days, on ‘Black Thursday’, the New York Times carried the headlines “PRICES OF STOCKS CRASH IN HEAVY LIQUIDATION, TOTAL DROP OF BILLIONS”. In an instant, the nations wealth seemingly vanished. Studebaker had weathered many recessions and depressions in its history and Erskine was confident the company would survive another. Even as conditions worsened he continued to express his belief that the market would eventually right itself and business would return to normal. Early on he was encouraged in this sentiment by positive reports from dealers. To keep the corporation strong while conditions improved, he authorized payment of substantial dividends on Studebaker stock. When things failed to improve, he continued to be optimistic and pay high dividends. To further aid in recovery he decided to reenter the low priced car market, still convinced, even after the failure of the ‘Erskine’, that small cars would make Studebaker.

1932 Rockne Six "75" by Studebaker - image courtesy of Larry Tholen

Erskine acquired a design developed for Willys-Overland, which ultimately was designated the 'Rockne Six'. A subsidiary corporation was created to manufacture and sell the 'Rocknes'. The new car was named for the famed Notre Dame football coach, who worked for Studebaker conducting motivational sessions for dealers. Coach Rockne died just days after completing an agreement to become more involved with Studebaker promotional efforts. His widow agreed that the new car be called 'Rockne'. The 'Rockne' sales performance was "pretty good" for a new marque, but it was the Great Depression and Studebaker had significant financial problems unrelated to the 'Rockne'. In 1933 Studebaker entered receivership, the receiver determined to reduce the number of Studebaker vehicle lines, and the 'Rockne' became expendable and was terminated in mid-1933. During its '32 & '33 model-year life - December 1931 through July 1933 - some 38,000 '32 and '33 Rockne cars and (in 1933) panel delivery trucks were produced.

By 1932 Studebakers sales had dwindled and its liabilities had well overrun its assets. Frantic to recover from an ever worsening predicament, Erskine sought a merger with the White Motor Company, a truck manufacturer. $14,000,000 in notes were issued to finance purchase of 95% of Whites stock only to have the merger blocked by some of White’s stockholders. Deeply in debt and unable to make commitments, the Studebaker Corporation was placed in receivership on March 21, 1933. On July 1st, Albert Erskine, despondent and broken, took his own life.

The 1933 Studebaker Commander

Harold Vance and Paul Hoffman, of Studebaker, and Ashton Bean of White Motor Company were appointed by the courts to be trustees in receivership. Their approach to recovery would prove to be much different than that of their predecessor. The first order of business was to inform the public that the company was still alive. Their released statement said, in part that “Studebaker carries on . . . The great South Bend plants of Studebaker, closed since the announcement of the bank moratorium, reopen Tuesday, March 21”. And open they did. During April, more than 3,800 cars were built and the company showed a profit of $20,000. While this was certainly positive it would not salvage the business. Debt was in the millions and running an auto firm took millions more. The most immediate need was retooling for the next years models. In order to increase money on hand, Pierce Arrow was sold for $1,000,000 cash. Vance and Hoffman then sought to further boost capital by going to the banks. The banking firm of Lehman Brothers, long associated with Studebaker, and seeing that the company and its new management had the ability to carry on, facilitated re-incorporating under Delaware law. The trustees then concerned themselves with labor. Both men were adamant that their work force be content and well paid and to this end, in mid 1933, allowed the United Auto Workers to unionize their plants. The Studebaker Chapter of the UAW would come to be known as Local 5. With the liquidation of the White Motor Company stock, Vance and Hoffman finally succeeded in building their working cash to almost $6,000,000. On March 9, 1935, Studebaker Corporation became the only automobile manufacturer to ever be released from receivership. Vance then became Chairman of the Board and Hoffman became President.

The 1939 Studebaker Champion brought the company out of the depression.

Being freed from the courts was one thing; restoring Studebaker to its former state was quite another. To affect a complete recovery, Vance and Hoffman realized that production numbers would have to be vastly increased. They also realized that achieving those numbers meant venturing into an area where Studebaker had failed twice before, the low-priced market. So in 1935 Studebaker embarked on a gamble. It aimed to produce a new, inexpensive car to be known as the ‘Champion’ and a large portion of ready capital was devoted to its development. Requiring four years and $4,000,000 to complete, Studebaker took care to ensure that the ‘Champion’ was not only inexpensive, but attractive and well engineered. Raymond Loewy Raymond Loewy immigrated to the United States shortly after World War I and took up design. A fashion designer at first, he eventually became involved in industrial design. Before his Studebaker connection he is credited with designing, among others, the art deco locomotive of the Pennsylvania Railroad. His association with Studebaker would last to the very end. designed the ‘Champions’ graceful interior and exterior while W. S. James (Roos’ successor) attended to the engineering. It was significantly lighter than other cars giving it improved gas mileage and even included such features as climate control. When the Champion was introduced to the public, in 1939, it was an instant success. Sales over the previous year nearly doubled with 72,000 units being built. By the end of the year, Studebaker was, once again, the largest independent auto maker in the country.

Raymond Loewy immigrated to the United States shortly after World War I and took up design. A fashion designer at first, he eventually became involved in industrial design. Before his Studebaker connection he is credited with designing, among others, the art deco locomotive of the Pennsylvania Railroad. His association with Studebaker would last to the very end. designed the ‘Champions’ graceful interior and exterior while W. S. James (Roos’ successor) attended to the engineering. It was significantly lighter than other cars giving it improved gas mileage and even included such features as climate control. When the Champion was introduced to the public, in 1939, it was an instant success. Sales over the previous year nearly doubled with 72,000 units being built. By the end of the year, Studebaker was, once again, the largest independent auto maker in the country.

1919 - 1939

The United States came through ‘The Great War’ with a sense of accomplishment. Now it was time to resume the ‘pursuit of happiness’. By 1919, horse drawn vehicle production was curtailed except for farm wagons and in 1920 Studebaker sold the wagon works to The Kentucky Wagon Mfg Co of Louisville. Everything pertaining to wagon and carriage manufacture was turned over including existing inventories of wagons. The remaining equipment, facilities and personnel were shifted to automobile production. In so doing, Studebaker became the only wagon maker to successfully transition to automobiles.

South Bend Plant 1 in the early 1920s. ( enlarge )

South Bend Plant 2 in the early 1920s. ( enlarge )

Up until 1920, all of Studebaker’s automobiles were being built at the former EMF factories in Detroit. Erskine’s pre-war plan to expand the South Bend factory had to be put on hold til war’s end with facilities only partiality complete. In march of 1919, construction resumed and by April of 1920 Plant 2 began the production of automobiles in South Bend. Plant 2 was an industrial show piece where most everything required to assemble cars was fabricated on site. The Detroit plant continued to produce the majority of Studebakers cars but, plans were made to eventually move a larger share of automobile assembly to South Bend.

The Light Six helped establish Studebaker's reputation.

Beginning in 1918 and continuing into the next decade, Studebaker built it's reputation around a line of six cylinder vehicles that vitalized it's growth. The `Big Six' was the deluxe series. It had a 60 hp engine and was offered as a tourer, sedan or coupe. The `Special Six' series was similar but was priced lower with a 50 hp engine. The `Light Sixes' were slightly smaller and economically priced with a 40 hp engine. Growth with Erskine at the helm was exceptional and the popularity of the sixes was evident as 51,000 automobiles were sold in 1920, 65,000 in 1921 and 150,000 in 1923. Commenting on the Sixes, Erskine said "these are the cars that made Studebaker famous".

Atalanta adorned the radiators of Studebaker's luxury line.

Detroit Plant 3 was eventually moved to South Bend. ( enlarge )

In 1926 the Detroit plant was finally relocated to South Bend. The man in charge was Harold Vance, who had been General Sales Manager since '23. With the move, he was promoted to Vice President for Production and Engineering and elected to the Board. That year another important addition was made to the executive staff. Out in Los Angles, a gentleman named Paul Hoffman

1891 - 1974

The 1927 Studebaker Erskine

With ample profits coming in, Studebaker sought to expand it's established line of models. Seeing the success of Ford’s Model-T and responding to consumer research and requests from dealers (even in Europe), Erskine felt Studebaker should enter the low price market and accordingly had engineers develop the ‘Erskine’. This handsome, little car, introduced in 1927, had a 40 horse power engine delivering 60 m.p.h. and 30 miles to the gallon but it was never the success it was hoped to be. A short engine life and a significantly higher price tag than it’s competitors added up to poor sales and the Erskine was discontinued within three years. Albert Erskine's venture in the opposite direction would prove to be more fruitful.

1931 President Eight State Brougham

1928 was a banner year for Studebaker. The poor showing in the small car market the previous year, would be offset by a development just coming to fruition. Concurrent with the little ‘Erskine’, Studebaker had been working on it’s first entry into the 8 cylinder market. Chief Engineer Delmar 'Barney' Roos, who had joined the company in 1926, was given the task of building a big 8 cylinder car and he gave Studebaker a genuine classic, the President 8

As the 20’s drew to an end America enjoyed unparalleled affluence. 1929 began on a financial upswing reaching a peak in late summer when the stock market topped out at an all time high. Then, early in October, stock prices began to drop. By October 22, banks and corporations nervously called in outstanding loans. Stockholders reacted in panic and frantically sold their holdings. Within two days, on ‘Black Thursday’, the New York Times carried the headlines “PRICES OF STOCKS CRASH IN HEAVY LIQUIDATION, TOTAL DROP OF BILLIONS”. In an instant, the nations wealth seemingly vanished. Studebaker had weathered many recessions and depressions in its history and Erskine was confident the company would survive another. Even as conditions worsened he continued to express his belief that the market would eventually right itself and business would return to normal. Early on he was encouraged in this sentiment by positive reports from dealers. To keep the corporation strong while conditions improved, he authorized payment of substantial dividends on Studebaker stock. When things failed to improve, he continued to be optimistic and pay high dividends. To further aid in recovery he decided to reenter the low priced car market, still convinced, even after the failure of the ‘Erskine’, that small cars would make Studebaker.

1932 Rockne Six "75" by Studebaker - image courtesy of Larry Tholen

Erskine acquired a design developed for Willys-Overland, which ultimately was designated the 'Rockne Six'. A subsidiary corporation was created to manufacture and sell the 'Rocknes'. The new car was named for the famed Notre Dame football coach, who worked for Studebaker conducting motivational sessions for dealers. Coach Rockne died just days after completing an agreement to become more involved with Studebaker promotional efforts. His widow agreed that the new car be called 'Rockne'. The 'Rockne' sales performance was "pretty good" for a new marque, but it was the Great Depression and Studebaker had significant financial problems unrelated to the 'Rockne'. In 1933 Studebaker entered receivership, the receiver determined to reduce the number of Studebaker vehicle lines, and the 'Rockne' became expendable and was terminated in mid-1933. During its '32 & '33 model-year life - December 1931 through July 1933 - some 38,000 '32 and '33 Rockne cars and (in 1933) panel delivery trucks were produced.

By 1932 Studebakers sales had dwindled and its liabilities had well overrun its assets. Frantic to recover from an ever worsening predicament, Erskine sought a merger with the White Motor Company, a truck manufacturer. $14,000,000 in notes were issued to finance purchase of 95% of Whites stock only to have the merger blocked by some of White’s stockholders. Deeply in debt and unable to make commitments, the Studebaker Corporation was placed in receivership on March 21, 1933. On July 1st, Albert Erskine, despondent and broken, took his own life.

The 1933 Studebaker Commander

Harold Vance and Paul Hoffman, of Studebaker, and Ashton Bean of White Motor Company were appointed by the courts to be trustees in receivership. Their approach to recovery would prove to be much different than that of their predecessor. The first order of business was to inform the public that the company was still alive. Their released statement said, in part that “Studebaker carries on . . . The great South Bend plants of Studebaker, closed since the announcement of the bank moratorium, reopen Tuesday, March 21”. And open they did. During April, more than 3,800 cars were built and the company showed a profit of $20,000. While this was certainly positive it would not salvage the business. Debt was in the millions and running an auto firm took millions more. The most immediate need was retooling for the next years models. In order to increase money on hand, Pierce Arrow was sold for $1,000,000 cash. Vance and Hoffman then sought to further boost capital by going to the banks. The banking firm of Lehman Brothers, long associated with Studebaker, and seeing that the company and its new management had the ability to carry on, facilitated re-incorporating under Delaware law. The trustees then concerned themselves with labor. Both men were adamant that their work force be content and well paid and to this end, in mid 1933, allowed the United Auto Workers to unionize their plants. The Studebaker Chapter of the UAW would come to be known as Local 5. With the liquidation of the White Motor Company stock, Vance and Hoffman finally succeeded in building their working cash to almost $6,000,000. On March 9, 1935, Studebaker Corporation became the only automobile manufacturer to ever be released from receivership. Vance then became Chairman of the Board and Hoffman became President.

The 1939 Studebaker Champion brought the company out of the depression.

Being freed from the courts was one thing; restoring Studebaker to its former state was quite another. To affect a complete recovery, Vance and Hoffman realized that production numbers would have to be vastly increased. They also realized that achieving those numbers meant venturing into an area where Studebaker had failed twice before, the low-priced market. So in 1935 Studebaker embarked on a gamble. It aimed to produce a new, inexpensive car to be known as the ‘Champion’ and a large portion of ready capital was devoted to its development. Requiring four years and $4,000,000 to complete, Studebaker took care to ensure that the ‘Champion’ was not only inexpensive, but attractive and well engineered. Raymond Loewy

| More Illustrations |